Intégrisme in Côte d'Ivoire

In the early 1990s, as Côte d'Ivoire navigated the turbulent transition to multiparty politics, a potent label entered the public discourse. The word intégrisme (integrism), originally used to describe Catholic fundamentalism, was suddenly and insistently applied to the nation's Muslim community, framing its members as a source of instability. This was not a spontaneous semantic shift but a calculated political strategy: during periods of democratic transition, ruling powers often consolidate their position by manufacturing a domestic "other," and the weaponisation of intégrisme served precisely this purpose.

Drawing on the Islam West Africa Collection corpus of 1,500 Islamic periodicals from Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d'Ivoire, and Togo from 1990 to the present day, this study analyses how state authorities and their allies deployed this terminology as a political instrument of marginalisation and control, and how Francophone Muslim intellectuals mounted a sophisticated counter-offensive. Their writings skilfully navigate Western secular discourses, Islamic theological concepts, and local African political frameworks to dismantle the label and produce novel understandings of religious commitment and political engagement.

Francophone Muslims intellectuals

The concept of the "Muslim intellectual" emerged as a distinct category in Francophone West Africa during the 1970s and 1980s, first appearing in Côte d'Ivoire. In this context, the "intellectual" is closely associated with university education; the term refers to Muslims who pursued a Western education in public secular or Christian schools before entering the civil service or formal economic sectors. This category is widely accepted among these individuals but typically excludes Arabic-speaking (Arabisants) religious scholars (ulama) trained at Islamic universities.

What sets these intellectuals apart is not their traditional Islamic knowledge (ilm) but their ability to engage in public discourse about Islam and society. They bridge divergent worlds, speaking to modern political contexts while addressing religious concerns. This dual fluency enables them to present Islam in a way that is accessible to educated urban populations while maintaining the necessary connections to traditional scholarship.

This group's most significant contribution has been to legitimise French as a language for Islamic discourse. This development was particularly transformative in Côte d'Ivoire, where French began to appear in mosque services by the late 1980s. These intellectuals have not only innovated linguistically but also carved out new spaces for Islamic discussion in academic and public venues, developing modern approaches to religious education and outreach.

These intellectuals position themselves as defenders of the Muslim community's interests. Leveraging their understanding of institutional contexts, they advocate for the professional, bureaucratic management of Muslim organisations, including regular elections and term limits. While they have not replaced traditional religious authorities, they represent a significant diversification of religious leadership. Through their publications and public engagement, Francophone Muslim intellectuals con

The emergence of a Francophone Islamic press

The sociopolitical liberalisation of the early 1990s, often termed the "press spring," catalysed a profound transformation in West African media. As press freedom expanded in countries such as Benin and Togo, a generation of young, Western-educated Muslims seized the opportunity to address a significant gap in community representation. These activists, associated with student movements such as the Association des Élèves et Étudiants Musulmans au Togo (AEEMT), Association Culturelle des Étudiants et Élèves Musulmans du Bénin (ACEEMUB), Association des Cadres Musulmans au Togo (ACMT), and Amicale des Intellectuels Musulmans du Bénin (AIMB), spearheaded the creation of a Francophone Islamic press, establishing platforms for viewpoints largely overlooked by the older leadership.

These periodicals are defined by their ability to bridge the sacred and the secular. Their coverage ranges from religious dogma and national Islamic news to socio-political analysis, cultural commentary, and international sport. This editorial breadth reflects the desire of Western-educated Muslims to engage fully with the public sphere rather than be overshadowed by traditional community structures. By balancing religious instruction with current affairs, these publications demonstrate the continued relevance of Islamic perspectives in modern contexts.

Crucially, these newspapers provide an independent platform for critical engagement. They offer an insider's perspective on the community while challenging the "gatekeepers" of umbrella Muslim organisations. While the content primarily reflects the worldview of Francophone intellectuals, the editors bridge a significant epistemological divide by featuring interviews with imams and preachers trained in the Arab-Islamic world. This synthesis makes traditional scholarship accessible to a modern French-speaking audience.

These publications often wield greater influence than their modest circulation figures suggest. Their willingness to voice communal frustrations and criticise state policy has repeatedly attracted government scrutiny. In Côte d'Ivoire, Plume Libre journalists were imprisoned in 1995 for their forthright criticism, and in Togo, Le Rendez-Vous editors have faced repeated official summonings. Such confrontations underscore the publications' political weight.

Ultimately, this platform enables Francophone Muslims to establish themselves as "Muslim intellectuals." By analysing socio-political issues through an Islamic lens, they have carved out a distinct space in the media landscape, transforming themselves from marginal voices into agenda-setters capable of shaping public opinion and redefining religious authority in the region.

The evolution of "scary" terms in the press

A quantitative analysis of the corpus reveals a striking chronological evolution in the terminology used to describe religious threats. References to intégrisme spike significantly during the Algerian Civil War (1991–2002), peaking around 1994–1995, the period of greatest violence. This correlates with a moment when the term dominated French and Western media coverage of Islamic movements. However, usage of intégrisme declined sharply after 2002. Terms such as terrorisme gained prominence in its place, particularly following the onset of the Mali War in 2012 and peaking during the crisis in Burkina Faso and the emergence of the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS). This linguistic shift suggests a transformation in public discourse: the anxieties of the 1990s concerning religious purity and political opposition have largely been replaced by contemporary fears of terrorisme and violent extremism.

From Catholic to Muslim "intégrisme"

To grasp the political weight of this discourse, one must trace the genealogy of the term itself. Originating in nineteenth-century France, intégrisme initially described a faction within Catholicism that vehemently opposed "modernist" attempts to reconcile Church doctrine with liberal philosophies. Derived from a theological defence of the "integrity" of tradition, the term denoted an uncompromising insistence on the purity of belief and a refusal to adapt to secular modernity.

Following the Iranian Revolution of 1979, Western observers sought a vocabulary to describe the resurgence of political Islam. As Martin Kramer notes, this search for terminology reflected a struggle to categorise distinct ideological currents. In the United States, the media adopted fundamentalism — a term rooted in American Protestant literalism of the 1920s — despite objections from scholars like Bernard Lewis, who argued it was historically inaccurate when applied to Islamic theology.

In the Francophone world, however, the debate took a different trajectory. French academics, seeking to avoid the Catholic baggage of intégrisme and the Americanism of fondamentalisme, resurrected the term islamisme (Islamism). Originally coined by Voltaire in the eighteenth century as a synonym for the religion of Islam itself, islamisme was repurposed in the 1980s by scholars such as Gilles Kepel to denote Islam as a modern political ideology.

Yet despite this academic shift, the outbreak of the Algerian Civil War in the early 1990s cemented the older term intégrisme musulman in the popular imagination. This semantic transfer did not occur in a vacuum. The collapse of the Soviet Union created a narrative void for Western powers, which soon identified a new ideological adversary. A narrative of a nouvelle croisade (new crusade) against Islam took shape, fuelled by the Iranian Revolution, the conflict in Palestine, and the political rise of the Front Islamique du Salut (FIS) in Algeria. These events were woven together to create a monolithic image of a dangerous Islam that provided a veneer of international legitimacy for the domestic deployment of anti-Islamic rhetoric. In the Francophone press, intégrisme became a catch-all pejorative for religious extremism, conflating pietist movements with violent insurgency. It was this emotionally charged label — laden with histories of French Catholic anti-modernism and colonial anxiety — that West African intellectuals found themselves forced to confront and deconstruct.

The politics of Intégrisme in the Ivoirian press

In the Ivorian public sphere, the term intégrisme functioned as a potent political weapon, particularly during the transition from the Houphouët-Boigny era to the presidency of Henri Konan Bédié. This period was marked by an intense power struggle between Bédié and his rival, Alassane Ouattara, whose dual identity as a Muslim and a Northerner—often pejoratively linked to Burkinabè heritage—became the focal point of a new, exclusionary nationalistic discourse known as Ivoirité.

Fraternité Matin: The Voice of the State

As the official state organ, Fraternité Matin played a pivotal role in legitimising the government's anxiety regarding Muslim political mobilization. The daily newspaper frequently published headlines that explicitly linked Islam with potential subversion, warning against the "scourge" of intégrisme.

A defining moment in this discursive strategy was the coverage of President Bédié’s tour of the north-west in July 1995. Fraternité Matin ran the headline "Préservons nos populations de l'intégrisme" ("Let us preserve our populations from integrism"), quoting the President’s warning against those who "transform a religion of peace into an instrument of death." By adopting this terminology, the state press drew a direct, albeit implicit, parallel between local political opposition and the violent Islamist insurgencies occurring globally, particularly in Algeria.

The newspaper used a dichotomous strategy to distinguish between 'good' and 'bad' Muslims.

-

The "Good" Muslim: Fraternité Matin heavily promoted figures like El Hadj Diaby Moustapha, president of the state-sanctioned Conseil Supérieur Islamique (CSI). In interviews, Moustapha was frequently quoted denouncing "all forms of integrism" and pledging loyalty to the state, reinforcing the narrative that obedience to the PDCI regime was synonymous with "true" Islam.

-

The "Bad" Muslim: Conversely, the newspaper gave ample space to government officials like Dr. Balla Kéita, who accused independent leaders—specifically those within the Conseil National Islamique (CNI)—of using religion "to satisfy unavowed ambitions." Fraternité Matin framed these autonomous movements not as civil society organizations, but as vectors for "intolerance" and "religious integrism," thereby justifying state surveillance and police interventions in mosques as necessary security measures.

Even when reporting on the grievances of the Muslim community, such as the denial of holidays or administrative harassment, Fraternité Matin often framed the state's response as benevolent protection against extremism. For instance, when reporting on Bédié's meetings with religious leaders, the paper highlighted his "reassurance" that "not all Muslims are integrists"—a rhetorical sleight of hand that, while ostensibly defensive, successfully cemented the association between the Muslim community and the threat of intégrisme in the public imagination.

The Opposition Press: Deconstructing the "Islamist Threat"

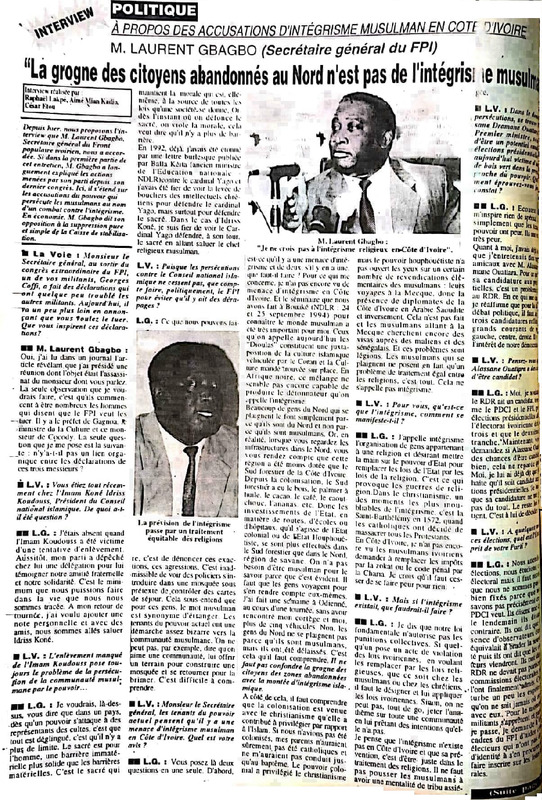

In contrast, opposition newspapers such as La Voie and Le Patriote offered a robust critique of this narrative. These publications argued that the spectre of intégrisme was a "diabolical plot"—a deliberate fabrication by the Bédié administration to disenfranchise Northern voters and justify the systematic removal of Muslim cadres from the civil service.

Rather than accepting intégrisme as a religious phenomenon, the opposition press reframed it as a political instrument. For instance, Le Patriote frequently highlighted how the term was used to "Satanise" Alassane Ouattara, arguing that the real danger to the republic was not religious fundamentalism but "tribal integrism" and state-sponsored xenophobia. Le Nouvel Horizon and La Voie meticulously documented police incursions into mosques and the "double standards" of a state that celebrated Christian political activism while criminalising its Muslim equivalent. By exposing these contradictions, the opposition press provided the intellectual scaffolding for a broader counter-offensive by Muslim intellectuals.

Reframing the narrative: The Muslim intellectuals' counter-offensive

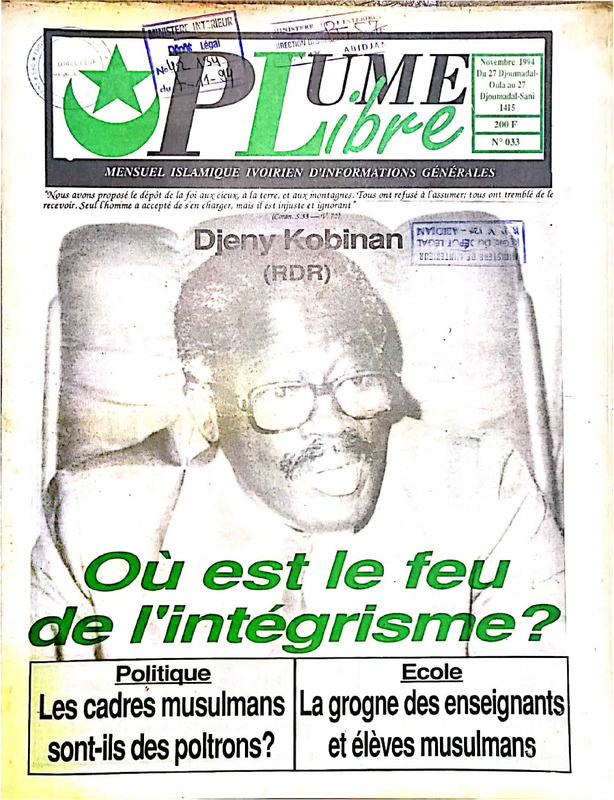

In the face of this weaponisation of language, the Francophone Islamic press did not remain passive. Publications such as Alif and Plume Libre launched a sophisticated intellectual counter-offensive, systematically dismantling the label of intégrisme to expose it as a tool of political exclusion rather than a legitimate religious descriptor.

Alif: Historical Deconstruction and "Tribal Integrism"

Adopting a pedagogical and analytical approach, Alif systematically stripped the term of its Islamic associations by tracing its etymological roots to Spanish Catholicism in 1892. The newspaper argued that applying the label to Ivorian Muslims was a deliberate historical misappropriation designed to marginalise a community seeking legitimate civil rights. Beyond semantic debates, Alif engaged in data journalism, publishing detailed lists of government appointees to demonstrate that the administration was dominated by specific ethnic groups.

Crucially, the writers at Alif inverted the government's rhetoric. They coined the term "intégrisme tribal" (tribal integrism) to critique the state's ethnic politics, arguing that regionalism and tribal nepotism—not Islam—posed the genuine threat to national cohesion. By framing the Muslim community's struggle as a quest for constitutional equality within a secular framework, Alif effectively countered the narrative that Muslims sought to establish a theocratic state.

Plume Libre: subverting the binary

While Alif adopted a pedagogical tone, Plume Libre engaged in a more combative and satirical critique, adopting an internationalist perspective to expose Western double standards. The newspaper frequently questioned why deep devotion in other faiths—such as Ronald Reagan's biblical rhetoric or the influence of the Catholic Church—escaped scrutiny, while similar expressions by Muslims were branded dangerous. Engaging with global events, particularly the crisis in Algeria, Plume Libre presented Islamic revival movements not as threats, but as legitimate expressions of cultural identity and decolonisation.

The publication's most significant theoretical contribution was its rejection of the false dichotomy between "moderate" and "intégriste" Islam. Plume Libre subverted the terminology by introducing the concept of "intégrisme laïque" (secular fundamentalist). Through this lens, the paper argued that rigid, state-imposed secularism had become a form of fundamentalism in itself—one that refused to tolerate religious diversity in public spaces, such as schools or the civil service. Editorialists argued that the "fire of integrism" existed only in the minds of politicians who refused to allow Muslims to organise autonomously outside the tutelage of the state. By labelling state interference and police aggression against mosques as the true extremism, Plume Libre effectively reversed the charge, framing the Muslim community’s struggle as a defence of democratic rights against an intolerant secular elite.

A Shared Vision

Together, these publications moved beyond mere defensiveness. By exposing the manipulation of language by political actors to disenfranchise citizens, they established themselves as guardians of true democratic values. They robustly defended the rights of Muslims while promoting interfaith understanding. Ultimately, they argued that the "problem" lay not in Islamic practice, but in a political system that relied on exclusion to maintain power.